Understanding Psychosocial Hazards

Psychosocial hazards refer to anything in how work is set up or managed that raises the chances of someone getting hurt mentally or physically. It is important that all employees understand these hazards and do their part to raise awareness of hazards in their work environment to managers and decision makers.

What are Psychosocial Hazards

Psychosocial is a term used to describe things that have both psychological and social features. Describing the intersection and interaction of social, cultural, and environmental influences on the mind and behaviour.

So, what are Psychosocial Hazards? Psychosocial hazards refer to anything in how work is set up or managed that raises the chances of someone getting hurt mentally or physically.

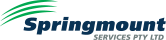

“A psychosocial hazard is a hazard that arises from, or relates to, the design or management of work, a work environment, plant at a workplace, or workplace interactions and behaviours and may cause psychological harm, whether or not the hazard may also cause physical harm. In severe cases exposure to psychosocial hazards can lead to death by suicide.” – Managing the Risk of Psychosocial Hazards at Work Code of Practice 2022

As shown in the figure below, psychosocial hazards are things at work that can cause harm by making a person feel stressed out for a long time, often and/or very strongly.

Stress here means how a person’s mind and body react to pressure or problems at work. This can include:

- feeling anxious or tense

- physical reactions such as changes in heart rate

Psychological harm or injuries are mental health problems that can show up in different ways, affecting how a person thinks, feels, acts, and interacts with others. These problems can be short-term or last for a long time, sometimes months or years. They can make it hard for a person to do their job well and impact their overall well-being.

COMMON PSYCHOSOCIAL HAZARDS

There are 14 common psychosocial hazards workers may encounter within the workplace. Worker’s often encounter a mix of psychosocial hazards, with some being constantly present while others occur less frequently. Below is a list of common psychosocial hazards that arise from or are related to work.

HIGH/LOW JOB DEMANDS

High Job Demands

High job demands means high levels of physical, mental or emotional effort are needed to do the job. It means more than sometimes ‘being a little busy’. High job demands become a hazard when severe (e.g. very high), prolonged (e.g. long term), or frequent (e.g. happens often).

High physical demands may include:

working long hours or without enough breaks.

having too much to do in too little time.

High mental demands may include:

not having the right skills or training for the task (e.g. junior workers given complex tasks).

High emotional demands may include:

exposure to aggression, violence, harassment or bullying.

displaying false emotions (e.g. being friendly to difficult customers).

Low Job Demands

Low job demands means sustained low levels of physical, mental or emotional effort are needed to do the job.

It is more than just having an occasional slow afternoon. Low job demands become a hazard when it is severe (e.g. very low demands), prolonged (e.g. long term) or frequent (e.g. happens often). For example:

long idle periods, particularly if workers cannot do other tasks (e.g. while waiting for necessary tools)

highly monotonous or repetitive tasks (e.g. packing products or monitoring production lines), or

workers cannot maintain their skills (e.g. not enough role specific tasks to keep competencies)

LOW JOB CONTROL

Low job control means workers have little control or say over the work. This includes over how or when the job is done. Low job control is more than being given work to do. It becomes a hazard when it is severe (e.g. very low job control), prolonged (e.g. long term) or frequent (e.g. happens often).

Low job control may include:

having little say over break times or when to switch tasks (e.g. work is machine or computer paced)

needing permission for routine or low risk tasks (e.g. ordering standard monthly supplies or sending a low-risk internal email)

strict processes that can’t be changed to fit the situation, or

workers level of autonomy doesn’t match their role or abilities (e.g. supervisors don’t have enough authority to do their jobs well)

POOR SUPPORT

Poor support means not getting enough support from supervisors or other workers, or not having the resources needed to do the job well. It is more than having to wait for someone to get out of a meeting to answer a non-urgent question. Poor support becomes a hazard when it is severe (e.g. very little support), prolonged (e.g. long term) or frequent (e.g. happens often).

Poor support may include:

not having the things needed to do the work well, safely or on time (e.g. limited tools or faulty IT systems)

not getting necessary information (e.g. information is unclear or not passed on in time)

not enough supervisor support (e.g. supervisors aren’t available to help, provide unclear guidance, take a long time to make decisions or are unempathetic)

LOW ROLE CLARITY

Lack of role clarity means workers aren’t clear on their job, responsibilities or what is expected. This may happen when they aren’t given the right information, or things keep changing. It is more than sometimes being given a complex task. Lack or role clarity becomes a hazard when it is severe (e.g. very little clarity), prolonged (e.g. long term) or frequent (e.g. happens often).

Lack of role clarity may include:

unclear roles and reporting lines (e.g. unclear who is responsible for what or who is working to which manager)

conflicting or frequently changing expectations and work standards (e.g. changing deadlines or contradictory instructions)

not being given information needed to do the job

POOR ORGANISATIONAL CHANGE MANAGMENT

Poor organisational change management means changes that are poorly planned, communicated, supported or managed. It is more than an unpopular change at work. Poor change management becomes a hazard when it is severe (e.g. very poor management), prolonged (e.g. long term) or frequent (e.g. happens often).

Poor organisational change management may include:

not consulting on changes (e.g. not talking to workers or genuinely considering their views)

poorly planned and communicated changes (e.g. changes are disorganised or do not have a clear goal information about the changes isn’t provided or is unclear)

not enough support for the changes (e.g. not training workers on how to use new tools)

LOW REWARD AND RECOGNITION

Inadequate reward and recognition mean there is an imbalance between the effort workers put in and the recognition or reward they get. Reward and recognition can be formal or informal. It is more than not winning an award at work. Inadequate reward and recognition become a hazard when it is severe (e.g. very little reward and recognition), prolonged (e.g. long term) or frequent (e.g. happens often).

Inadequate reward and recognition may include:

not enough feedback or recognition (e.g. workers don’t receive feedback on their work or guidance on how to improve)

unfair negative feedback (e.g. criticism on things that are not within a workers control or that they haven’t been taught how to do)

limited development opportunities, or not recognising workers’ skills (e.g. micromanaging simple tasks)

POOR ORGANISATIONAL JUSTICE

Poor organisational justice means a lack of procedural justice (e.g. fair decision-making processes), informational fairness (e.g. keeping everyone up to date and in the loop), or interpersonal fairness (e.g. treating people with dignity and respect).

It is more than a worker sometimes not getting the shift they asked for. Poor organisational justice becomes a hazard when it is severe (e.g. very poor organisational justice), prolonged (e.g. long term) or frequent (e.g. happens often).

Poor organisational justice may include:

poor handling of workers information (e.g. not keeping personal information private)

policies or procedures that are unfair, biased or applied inconsistently (e.g. favouritism when assigning ‘good’ shifts)

failing to appropriately address (actual or alleged) issues (e.g. underperformance, misconduct, or inappropriate or harmful behaviour such as bullying)

REMOTE OR ISOLATED WORK

Remote or isolated work means work that is isolated from the assistance of others because of the location, time or nature of the work. It often involves long travel times, poor access to resources, or limited communications.

It is more than not getting mobile reception in the lift at the office. Remote or isolated work may include:

working alone (e.g. cleaning an office afterhours)

work where it is hard to get help in an emergency

having limited access to resources (e.g. infrequent deliveries and long delays for new supplies)

reduced access to support networks or missing out on family commitments (e.g. working fly-in fly-out)

POOR ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS

A poor physical environment means workers are exposed to unpleasant, poor quality or hazardous working environments or conditions. It is more than the office being a little chilly first thing on a cold morning. A poor physical environment becomes a psychosocial hazard when it is severe (e.g. very poor or hazardous), prolonged (e.g. poor long term) or frequent (e.g. often poor).

Poor physical environments may include:

performing hazardous tasks or working in hazardous conditions (e.g. work at heights or near unsafe machinery or hazardous chemicals)

doing demanding work while wearing uncomfortable PPE or other equipment (e.g. PPE is poorly fitted, heavy, or reduces visibility or mobility)

working with poorly maintained equipment (e.g. equipment that has become unsafe, noisy or started vibrating)

TRAUMATIC EVENTS

Witnessing, investigating or being exposed to traumatic events or materials is a psychosocial hazard. Something is more likely to be traumatic when it is unexpected, seems uncontrollable or is caused by intentional cruelty. Traumatic events or materials become a hazard when they are severe (e.g. very traumatic), prolonged (e.g. long term) or frequent (e.g. happens often).

Traumatic events or materials may include:

witnessing or investigating a fatality, serious injury, abuse, neglect or other serious incident (e.g. working in child protection)

being afraid or exposed to extreme risks (e.g. being in a car accident)

exposure to natural disasters (e.g. emergency service workers responding to a bushfire)

HARMFUL BEHAVIOURS

Harmful behaviours can harm the person they are directed at and anyone who witnesses the behaviour. They include:

Violence and aggression – Workplace violence and aggression are when a person is abused, threatened or assaulted at the workplace or while they’re working.

Bullying – Workplace bullying is repeated, unreasonable behaviour directed at a worker (or group of workers).

Harassment – including sexual and gender-based harassment, racism, ablism, agism, and

Conflict or poor workplace relationships and interactions.

It is more than someone forgetting to say good morning one day. Harmful behaviours become a hazard when it is severe (e.g. very harmful), prolonged (e.g. long term) or frequent (e.g. happens often).

Managing Psychosocial Hazards

Springmount’s Responsibility

Now that you understand what psychosocial hazards can look like, we will discuss Springmount’s responsibility for managing psychosocial risks within the workplace.

Managing the Risk of Psychosocial Hazards at Work Code of Practice 2022

In 2022 the Queensland Government released the Managing the Risk of Psychosocial Hazards at Work Code of Practice.

This new code of practice has been introduced to provide employers with information on what psychosocial hazards and risks are, and how they can be controlled and managed within their workplaces. The code further assists employers with understanding what reasonable actions can be taken to reduce risks and mitigate the impact of harm for psychosocial hazards that cannot be reasonably eliminated from workplaces.

The code of practice also provides an avenue for employees to take legal action if they have been exposed to psychosocial hazards and have reported them to their employers, but their concerns have not been addressed as is reasonably practical or required by their employer under the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (WHS Act).

Springmount as defined by the WHS Act is an entity or Person Conducting a Business or Undertaking (PCBU) and must comply with the responsibilities and procedures outlined by the Psychosocial code of practice.

Namely Springmount and its Officers must:

- Eliminate or minimise health and safety risks, and psychosocial hazards in the workplace so far as is reasonably practicable.

- Effectively manage psychosocial hazards where they have been identified.

- Adopt and utilise a risk-management system which includes the identification and elimination of psychosocial hazards and implement control measures to eliminate or minimise risks and regularly review these measures to ensure they are effective.

- Consider how all systems both physical and social interact within the company to eliminate and minimise risks.

Some examples of what this could look like for Springmount include:

- Ensure employees are provided with the necessary training, and information to fulfil their roles.

- Ensure that there are adequate amounts of instruction and supervision to support workers to complete their tasks safely effectively e.g., when using heavy machinery.

- An adequate roster of employees is scheduled to carry out tasks required on site.

- Complaints about psychosocial hazards are assessed and responded to in a timely manner.

Staff Responsibility

Now that you understand what Springmount’s responsibilities are for managing psychosocial risks within the workplace, we will discuss what responsibilities staff have within the workplace.

Duties of workers

While at work, a worker must:

- take reasonable care for their own health and safety, including psychological health

- take reasonable care their acts or omissions do not adversely affect the health (including psychological health) and safety of other persons

comply, so far as the worker is reasonably able, with reasonable instructions given by a PCBU - cooperate with reasonable health and safety policies or procedures issued by a PCBU that have been notified to workers.

Some examples of what this could look like for staff include:

- Taking regular breaks to avoid feeling overwhelmed and stressed and using protective equipment properly to prevent physical injuries.

- Following supervisor instructions and safety protocols when handling cleaning chemicals, ensuring oneself and coworkers are safe.

- Following the Springmount’s health and safety guidelines, such as reporting any hazards or incidents immediately, to help maintain a safe work environment for everyone.

Responding to Psychosocial Hazards

As employees you may at some point have a complaint or concern regarding a psychosocial hazard. Therefore, it is important that you understand the steps involved in raising a concern and how Springmount will condcut and process your concern while adhering to the guidelines specified by the WHS act and Springmount.

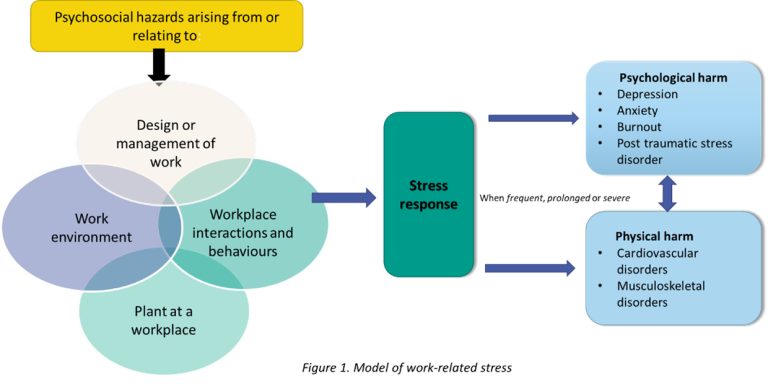

The Managing the Risk of Psychosocial Hazards at Work Code of Practice operates under the 2011 WHS act, and it stipulates that any complaints or grievances associated with psychosocial hazards be handle in the same manner as any other WHS complaint, with some exceptions (e.g. a notifiable incident, more information in the next section).

The WHS Act provides a legal framework for resolving work health and safety issues. This includes issues regarding risks to workers from psychosocial hazards. The intent is for the parties involved to resolve the issue between themselves in the first instance. However, where attempts to resolve the issue through initial discussions are unsuccessful, the WHS Act and WHS Regulation provide steps that must be followed to resolve the issue.

Springmount’s WHS Issue Resolution Process

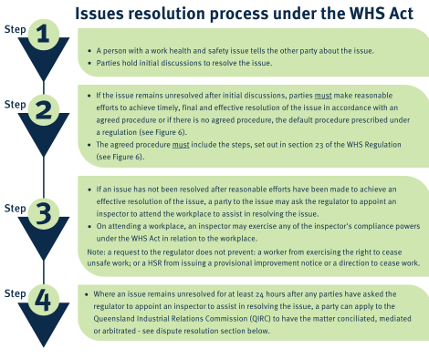

If you have identified a hazard and it is not of an emergent nature, you can follow Springmount’s Employee Grievance and Dispute Resolution Procedure, which has been developed in accordance with the WHS Act. You can see this below or find a printable copy on the staff portal here.

Notifiable incidents

Please note. In the case of a serious incident, you must notify your supervisor right away. Do not attempt to resolve the issue yourself.

Springmount is required to notify the regulator right away after learning of a serious incident and keep the site as is until an inspector arrives. A serious incident includes someone’s death (like from suicide) or a severe physical or mental injury that needs immediate hospital treatment (such as a serious head injury from workplace violence).

Figure 3. Springmount’s Employee Grievance and Dispute Resolution Procedure

What can you do?

As an employee, the best thing you can do is be aware of the potential psychosocial hazards in your environment and, if you have a concern, raise that with your supervisor.

RESOURCES

Below are some resources you can access or recommend for mental health and wellbeing support to your colleagues.

EMPLOYEE ASSISTANCE PROGRAM

Springmount Services has engaged EAP Assist to provide counselling assistance to all Springmount Services employee’s free of charge for up to three visits of one hour each over a 12-month period.

The aim of counselling with EAP Assist is to help resolve both workplace and personal issues before they adversely impact your personal wellbeing and work performance.

To request up to three hours of telephone counselling you can use Springmount Services dedicated Helpline number: 0407 086 000.

Alternatively, you can go to the EAP Assist website eapassist.com.au/booking-form/ to request an appointment.

EAP Assist counsellors are all highly experienced and will initially ask for your name as well as that of your employer in order to confirm eligibility for services. Information obtained during counselling is confidential and will not generally be released to a third party without prior consent.

The EAP Assist website also contains an extensive range of self-help resources which all employees are encouraged to use. Please go to: https://eapassist.com.au/

HELPLINES

If you or a colleague are feeling depressed, stressed or anxious there are services to help.

- Beyond Blue Aims to increase awareness of depression and anxiety and reduce stigma.

Call 1300 22 4636, 24 hours/7 days a week, chat online or email. - FriendLine Supports anyone who’s feeling lonely, needs to reconnect or just wants a chat. All conversations with FriendLine are anonymous. You can call them 7 days a week on 1800 424 287, or chat online with one of their trained volunteers.

- Lifeline Provides 24-hour crisis counselling, support groups and suicide prevention services. Call 13 11 14, text on 0477 13 11 14 (12pm to midnight AEST) or chat online.

- MensLine A professional telephone and online counselling service offering support to men. Call 1300 78 99 78, 24 hours/7 days a week, chat online or organise a video chat.

- SANE Australia Provides support to anyone in Australia affected by complex mental health issues, as well as their friends, family members and health professionals. Call 1800 18 7263, 10am – 10pm AEST (Mon – Fri), or chat online.

- Suicide Call Back Service Provides 24/7 support if you or someone you know is feeling suicidal. Call 1300 659 467.